by Beberly T. Calugan

The observances of All Saints’ Day and All Souls’ Day hold significant meaning across various Christian denominations, with different customs and levels of recognition. All Saints’ Day, declared by Pope Gregory IV on November 1st, honors all saints, not just martyrs, and is marked by church services, prayers, and region-specific traditions (Crain, 2024; Britannica, 2024). Meanwhile, All Souls’ Day, observed on November 2nd, originated in the 11th century under Saint Odilo of Cluny, who instituted a day of remembrance for the departed faithful, a practice that later spread through the Catholic Church (SCJ Philippines Region). While these observances are widely practiced by Catholics and Orthodox Christians, their recognition varies in Anglican and Lutheran traditions. Some Protestant denominations may acknowledge these days but with less ritualistic significance compared to their Catholic counterparts (Bible Study Tools, 2024).

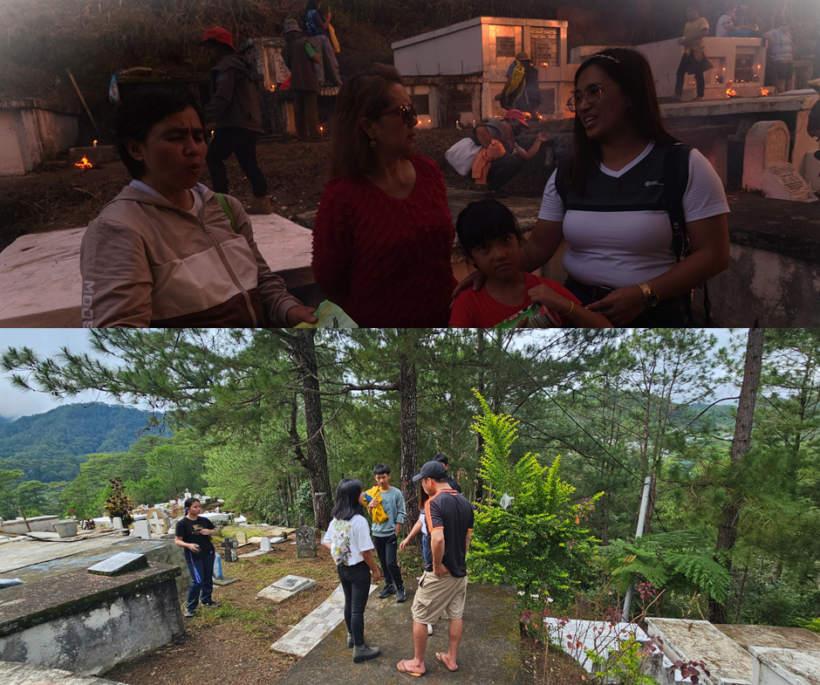

Saleng or sa-eng (Sagada term) or salvage woods used during panag-aapoy or panagdedenet.

All Saints’ Day and All Souls’ Day are widely observed as holidays in many countries, especially in Western and Central Europe, and in the Philippines. These days serve as moments of remembrance for the departed, where people honor their loved ones through various customs such as visiting cemeteries, lighting candles, praying, and offering tributes. These practices are often deeply rooted in cultural traditions and provide an opportunity for individuals to express gratitude for the lives of those who have passed.

In Sagada, Mountain Province, there is a distinct cultural tradition that sets the community apart. Rather than using candles, the people of Sagada illuminate their tributes with “saleng” (fatwood), which is a resinous wood sourced from the roots or lower trunks of mature Benguet pine trees, found in the highlands of Northern Luzon. Saleng is a material of great cultural and practical value to the indigenous people of the Cordillera region. Traditionally, it served as a light source at night, as well as a fire starter for cooking, illustrating its functional significance to the community long before its use in honoring the deceased.

The Sagada people have a distinctive and creative way to honor and remember their departed loved ones. Adapting their traditions to the resources available in their mountainous region, they use saleng to ignite bonfires near or at each tomb. Saleng is particularly able to withstand strong winds and rains, as experienced in the province during November. Although saleng remains a popular choice, they also make use of salvage or waste wood to keep bonfires burning.

As the night falls, a breathtaking display unfolds: the panag-aapoy, a fiery tribute to ancestors. This practice rooted in ancient Sagada rituals is a poignant tribute to the departed observed every first of November. The Panag-aapoy or Panagdedenet, a kankana-ey meaning “the tradition of lighting fires,” is a fascinating event. It continues to still captivate tourists visiting Sagada on All Saints’ Day.

Sharing stories and exchanging laughter strengthen our bonds. It’s a timeless tradition that links us to our past and inspires us for the future.

In Chinese culture, flowers have been very essential in symbolizing growth, life, and continuation of lineage and family; by taking care of the graves, planting flowers, families honored their ancestors and departed loved ones (Flower Chimp, 2024). Similarly, Sagada people’s deep connection to their ancestors and their environment is profoundly expressed in the panag-aapoy, which is more than just a cultural spectacle. “The feelings of remembrance and gratitude for the lives of departed loved ones become more intense as the flames grow larger,” Engr. Francis O. Tauli, Vice Governor of Mountain Province, explained. It unites families and tightens social bonding as people share stories, food, laughter, and heartfelt tributes to their loved ones.

Witnessing the amazing panag-aapoy, I remembered my grandfather, who instilled in me the value of education. It was a bittersweet moment—filled with joy and gratitude for their love and guidance, yet tinged with sadness as I reflected on their profound impact on my life.

While this is a culture-deep practice, its impact on the environment is crucial to consider, especially on the possibility of deforestation. To mitigate this, the Sagada people adhere to sustainable practices, the Batangan, a traditional system of forest management that protects, rehabilitates, and develops the area. Recognized members of the community, clan, or family are responsible for ensuring the sustainable use of forest resources for both present and future generations. The practice of selective cutting maintains available resources while allowing for regenerations. Additionally, the saleng for the panag-aapoy is sourced from the roots of old Benguet pine trees cut one year or more ago. To further minimize environmental risks and ensure the safety of the people during the panag-aapoy, strict fire safety rules are enforced by the Bureau of Fire Protection and the Philippine National Police to prevent accidents.

The practice of panag-aapoy can be viewed through the lens of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly SDG 11, sustainable cities and communities (United Nations, n.d.). The Sagada community enhances its identity and nurtures a sense of community by preserving and fostering this cultural legacy. This fosters the sustainability of growth and the general welfare of the community.

Furthermore, the panag-aapoy can serve as a concrete manifestation of Target 11.4, which further strengthens efforts to protect and safeguard the world’s natural heritage. The Sagada people are committed to helping attain this worldwide aim through contributions by preserving this culture, whether it is through community activities, local government assistance, or tourism initiatives.

Showcasing the abundant Benguet pine trees in Sagada, nestled in the majestic Cordillera Mountains. These towering trees, with their glossy green foliage, enhance the region’s beauty, provide homes for wildlife, and support ecological balance. Valued culturally and economically, their saleng wood is essential in traditions like Panag-aapoy.

As a Sagada native, I found it heartwarming to reminisce about my childhood evenings during the panag-aapoy, gathering with my father’s siblings and cousins to honor our cherished grandparents. It’s wonderful to see younger generations participating in this tradition with enthusiasm. My children, for instance, were captivated by the experience. My daughter exclaimed, “I now understand what you’ve always been telling us about the panag-aapoy. We’ve really enjoyed it! It’s amazing to have a tradition like this. Thank you, Mom, for sharing this with us and explaining its significance.” My son added, “I can’t wait to tell my friends about the panag-aapoy. It’s so unique to use saleng instead of candles!”

Children’s smiles, glowing as brightly as the saleng fire, lighting up the cemetery with warmth.

The panag-aapoy is a testament to the resourcefulness and ingenuity of the Igorot people. It is a tradition that has persisted through many generations, evolving with the times while preserving its core essence. As we continue to celebrate this cultural legacy, let’s ensure that future generations can uphold this age-old custom, experience the wonders of the panag-aapoy, and carry forward this timeless tradition.

The panag-aapoy is a sacred tradition for the Sagada people and should be treated with respect and sensitivity. While it provides a unique cultural experience for tourists, its religious nature must not be exploited commercially. To preserve the integrity of the tradition, responsible tourism should be encouraged, and visitors should respect local customs to maintain the authenticity of the panag-aapoy for centuries to come.

A video showing the panag-aapoy or panagdedenet in Sagada, Mountain Province. https://youtu.be/fJaxPbg0QU4. Video credited to Janzeen T. Calugan

The author and her family enjoyed a heartfelt trip to Sagada to celebrate Undas (the Filipino tradition of All Saints’ Day and All Souls’ Day)—a special occasion to honor their ancestors who have gone before them while cherishing the promise of the future.

As we bid farewell to Sagada, my heart overflows with gratitude and fulfillment. Witnessing the remarkable panag-aapoy once again has deepened my connection to my roots and created unforgettable memories for my family. This beautiful cultural tradition of honoring ancestors and cherishing their lives is truly inspiring.

References:

Bible Study Tools. (2024). Are All Saints’ Day and All Souls’ Day the same? https://www.biblestudytools.com/bible-study/topical-studies/are-all-saints-day-and-all-souls-day-the-same.html.

Britannica. (2024). All Souls’ Day | Description, History, & Traditions. https://www.britannica.com/topic/All-Souls-Day-Christianity

Crain, A. 2024. Christianity. All Saints’ Day – The Meaning and History Behind November 1st Holiday. https://www.christianity.com/church/church-history/all-saints-day-november-1.html#history

Flower Chimp Hong Kong. (2024, April 03). Best Flowers For The Qingming Festival. https://www.flowerchimp.com.hk/collections/popular-this-week. Retrieved November 2, 2024.

SCJ Philippines Region. All Saints’ and All Souls’ Day in the Catholic Church: A Time of Remembrance and Communion. https://scjphil.org/2024/11/01/all-saints-and-all-souls-day-in-the-catholic-church-a-time-of-remembrance-and-communion.

Tauli, F. O. November 1, 2024. Personal conversation about the Panag-aapoy. Sagada, Mt. Province.

United Nations. (n.d.). Sustainable Development Goal 11: Responsible consumption and production. https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal11.

About the author:

Beberly M. Tauli-Calugan, a dedicated public servant at the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR), hails from the picturesque town of Sagada, Mountain Province. Her upbringing in this culturally rich region instilled a deep appreciation for diligence, driving her strong work ethic and unwavering commitment to excellence.

Beberly M. Tauli-Calugan, a dedicated public servant at the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR), hails from the picturesque town of Sagada, Mountain Province. Her upbringing in this culturally rich region instilled a deep appreciation for diligence, driving her strong work ethic and unwavering commitment to excellence.

About the Editor:

Genevieve Balance Kupang is an applied cosmic anthropologist and a certified cultural mapper, currently serving as BCU’s Dean of the Graduate School and International Relations Officer. She is a member of Grupo Kalinangan, focusing on cultural heritage conservation through innovative IT tools and services, building capacities, and leveraging support systems. As a board member of the World University Network of Innovation (WUNI)-Leaders, she fosters global collaboration. She explores the intersections of culture, arts, peace, justice, integrity of creation, interfaith dialogue, curriculum, and instruction. One of her greatest joys is empowering learners to realize their potential and encouraging them to share their unique voices with the world.

Genevieve Balance Kupang is an applied cosmic anthropologist and a certified cultural mapper, currently serving as BCU’s Dean of the Graduate School and International Relations Officer. She is a member of Grupo Kalinangan, focusing on cultural heritage conservation through innovative IT tools and services, building capacities, and leveraging support systems. As a board member of the World University Network of Innovation (WUNI)-Leaders, she fosters global collaboration. She explores the intersections of culture, arts, peace, justice, integrity of creation, interfaith dialogue, curriculum, and instruction. One of her greatest joys is empowering learners to realize their potential and encouraging them to share their unique voices with the world.